Summer Jam Extra

In the Beer Garden with David Favela

Get to know David Favela on his own terms on his own turf—in the beer garden of Border X Brewing in Barrio Logan, San Diego. In this extended interview, the Chicano CEO and brewery owner shares his backstory in the technology industry, his hot takes on culture and sustainable development, and why his community needs a Chicano 2.0. Plus, meet Yanel de Angel, managing director of Perkins&Will’s Boston studio and the genius behind ResilientSEE, a collaborative initiative to restore and sustain communities throughout her first home, Puerto Rico.

Show Notes

Yanel de Angel is principal and managing director of Perkins&Will’s Boston studio. She is the first Latina managing director in the firm’s history and the founder of the resilientSEE initiative in Puerto Rico. Her expertise in higher education environments focuses on student life projects, for which she conceptualizes buildings as teaching laboratories where sustainability and design are intertwined. In addition to being an active member of Perkins&Will’s Resilience Lab, Diversity Council, Executive Committee, and Project Delivery Board, Yanel is vice president of Practice for the Boston Society of Architects (BSA)/AIA Board, co-chair of the BSA Women in Design (WiD) Award of Excellence committee, and co-founder of the BSA WiD Mid-Career Mentorship committee.

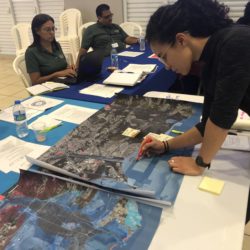

In the episode, Yanel describes her resilientSEE initiative and the success of its “gentefication” strategies in the Toa Baja, Guánica, and Humacao municipalities of Puerto Rico.

ResilientSEE was born in 2018, after hurricanes Irma and María caused catastrophic damage throughout Puerto Rico. Thousands were left without basic necessities, hundreds without power. Roofless homes collapsed. Roads became inaccessible. Yanel responded by spearheading a campaign to attract a range of partners—from academia, private industry, and the nonprofit and civic realms—to devise implementable strategies for social (S), economic (E), and environmental (E) recovery.

Five years later the global alliance continues to provide resilient design and planning in support of long-term relief for the island’s communities. Ongoing projects range from municipal- to neighborhood- and community-scale interventions and include educational programs. The initiative has also expanded to design climate-adaptation strategies in other geographic locations.

David Favela is founder and CEO of Border X Brewing and Director of the federal Build to Scale initiative at the University of California San Diego.

In the episode, David mentions the origin story of Hewlett Packard, where he worked for 20 years before starting Border X Brewing.

He also recounts the story of Cirque du Soleil from the book Blue Ocean Strategy (2005), which gave him the idea to do beer his own way.

Maybe you’ve heard the term “placemaking.” Used broadly since the 1960s, placemaking centers the idea that we’re not just designing spaces, but, rather, places. Key planning figures such as Jane Jacobs and Holly Whyte were placemaking advocates. Before long, initiatives such as the Project for Public Spaces advocated for “creative placemaking” applications in the built environment.

More recently, “placekeeping” has emerged to emphasize what David and Yanel both point out in the episode, that “we aren’t making something out of nothing.” Advocates for placekeeping are calling out the exclusionary and harmful implications of “making” places as though they weren’t already places to begin with. The new term helps legitimize the assets of space and culture that are already there.

Roberto Bedoya, the Cultural Affairs manager for the City of Oakland, California, offers a definition that embeds the experience of place in the relationships it creates:

“Placekeeping is about knowing your locale, knowing where you stand, where you sit, what is your relationship to your neighbors? What is your relationship to the sky? What is your relationship to the folks coming out of the neighborhood bar? Those relationships are keeping you wanting to keep those things alive.”

This exhibit, part of a colloquium on place and equity in museum design, further expands the critical conversation around space, place, and relationships with two more terms: “placesharing” and “placefeeling.” Both center the human experience and call out the barriers to equitable access.

David talks candidly about the “colonial mindset,” a cultural framework he confronts and tries to unlearn every day. This article refers to the colonial mentality as a term that “represents internalized cultural inferiority,” whereby colonization of a region, or culture, permeates deep into the way we approach our environments. It might show up as imposter syndrome, as David describes, where certain people may not feel worthy of success because the colonizing culture devalues their ethnicity or class.

In this article Mukoma Wa Ngugi reflects on his father’s 1986 book Decolonizing the Mind, about education in Nigeria and the importance of writing in one’s mother tongue. David makes the same argument at Border X Brewing, emphasizing how critical it is that his beers and his space speak the language of the people who have been in Barrio Logan for generations.

The flavors are a design decision, Erika declares. David and Border X Brewing have intentionally and thoughtfully embraced the “coolness” of Chicano culture, applying it directly to the beers they brew, from the Pepino Sour that we fell in love with to Abuelita’s Chocolate.

In the episode he tells the story of their first big design success, the Border X Blood Saison, which was inspired by the traditional Mexican drink agua de jamaica. Here’s a recipe for a refreshing and tasty agua de jamaica you can try on your own.

When Erika asks where David got his courage as an entrepreneur of color, he says art and shouts out the local musicians, the Roots Factory, and Chris Zertuche of La Bodega Gallery.

At the end of the interview, David leaves us with a glimpse of his future and the provocative idea of “Chicano 2.0.”

The Chicano activists of the 1960s formalized their political vision and objectives into El Plan Espiritual de Aztlan.

As David suspected, El Plan de Ayala goes back to the Mexican Revolution. The “chicano” goes back at least as far as the jacket clubs he references in his quick history of Barrio Logan.

This episode features music courtesy of Epidemic Sound:

“Vacaciones” and “Dia de Playa” by Timothy Infinite

Transcript

Summer Jam Episode 4: “In the Beer Garden with David Favela”

[Fade in sounds of birds chirping in the back beer garden of Border X Brewing in Barrio Logan, San Diego.]

[Cue in “Vacaciones” by Timothy Infinite/Epidemic Sound]

Erika Eitland: This was great. Wow.

Eunice Wong: I have so many warm fuzzy feelings…We killed it.

Erika Eitland: Yeah. Oh my god…

Eunice Wong: Everything is so great.

Erika Eitland: Oh we get another one!

David Favela: [Laughter.]

Erika Eitland: Ah, alright.

David Favela: It’s just a taster, right? You guys’ll be fine.

Erika, Eunice, and Monica, in unison: Inhabit is a show about the power of design.

[Music drops to “Vacaciones” Drum and Melody stems only]

Yanel de Angel: Hello, Inhabit listeners. Buenos días. Hola. This is such a treat to introduce the finale of Inhabit Summer Jam, the complete interview with Border X Brewing CEO David Favela. Can’t wait. My name is Yanel de Angel. I am an architect here at Perkins&Will and the managing director of the Boston studio. This second Inhabit series fills me with pride. It’s all about what we can learn from David Favela about how he is building his brewery business with, alongside, and for the chicano community of Barrio Logan. I am not a chicana. I am puertorriqueña! Boricua! And I recently became the first Latina managing director of any studio in the entire firm. When David talks about creating a space where he can be really good at being Mexican, where his neighbors and community can feel like they are cool, and their culture is cool—I feel a renewed sense of purpose as an architect.

[“Vacaciones” Melody stem fades out and Instrument stem fades in over Drums]

Our profession makes a critical distinction between spaces and places. In recent years, we have started to have lots of conversations about whether we should be placemaking or placekeeping. As I listen to David talk about understanding, honoring, and supporting what is already there, I hear how fundamental the placekeeping intervention is. We really are not building something out of nothing, but like Eunice said, the goal is not to avoid any change. Change needs to be woven into the strengths of the existing community to honor their longtime investment in that place. In this conversation with Erika, we also hear David reclaim developments dirty word, “gentrification” with “gentefication,” from “gente,” the Spanish word for “people.” He breaks it down into three best practices: prioritizing what is already in the neighborhood, authentic storytelling, and investment in economic opportunity for the neighborhood. These three ingredients resonate with me, particularly now that we are rebuilding communities everywhere in the wake of extreme weather events such as Hurrican Ian—

[“Vacaciones” full mix returns]

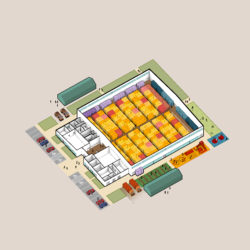

but especially in my beloved Puerto Rico since Maria and now Fiona. In 2017, I launched an initiative called ResilientSEE—capital S-E-E, for social, environmental, and economic resilience—and we continue to be active and engaged in the communities we began to rebuild five years ago. What I love about David’s three ingredients is that they are fundamental to doing this kind of work. Our lessons from Puerto Rico will sound very familiar. Number one, we are not starting from scratch so we work with the physical assets the community already has. For example, transforming a decommissioned elementary school into a resilient energy center in Barrio Arenas, Guánica municipality. This transformation is about giving an old soul new life through structural stabilization, new plumbing and electric system, and a new community kitchen. Number two, the community is the author of their own storytelling. We are there to augment and amplify those voices through empowerment and advocacy. When we met for the first time with community leaders in the Toa Baja municipality, they expected us to tell them what needs to be done. Instead, we said, “You are the expert. You live here. Give us your insights, and let’s co-author a solution together.” It’s just better when we do it together. And number three, economic opportunity is only sustainable if it is rooted in the neighborhood. We need to support community entrepreneurship. Sometimes that means high schoolers making cool T-shirts with great colors to support themselves and contribute to their community. Like David and Border X in Barrio Logan, we are succeeding in Puerto Rico—in Barrio Arenas Guánica, Toa Baja, and Humacao communities to mention a few—because gentefication and placekeeping work. Impact-aware, culturally specific design allows authentic places to grow and sustain. Or, to quote the Summer Jam tagline, Design is culture and soul. Alma! But as provocative as their conversation about gentefic ation is, Erika and David touch on so many aspects of design at the human scale—food, feeling, history, activism—you will want to listen all the way through. Entonces, en el jardín de la cerveza con David Favela.

[“Vacaciones” fades out. Laughter and sound of helicopter in the beer garden fades in. Throughout interview, occasional murmurs and doors closing inside brewery can be heard.]

Erika Eitland: Awesome.

Eunice Wong: I think we’re fine.

David Favela: Sorry, there’s a military base nearby.

Eunice Wong: That’s fine. It’s adding to the—

David Favela: The ambience!

Eunice Wong: Yeah, the ambience. [Laughter]

Erika Eitland: Where are we? Yeah. Good to go? Alrighty. So we’re just gonna get into it. So thank you for having us. We’ve known each other what, two days?

David Favela: Yeah.

Erika Eitland: Yeah, two days, two hours of those two days. So we’re really working hard on this friendship already. And so I just want to place people for everyone who’s listening. Where are we? What’s your name?

David Favela: Perfect. So my name is David Favela, I’m the CEO of Border X Brewing. We’re currently sitting in the back beer garden of Border X Brewing here in beautiful Barrio Logan. It’s a nice, sunny, windy day—

Erika Eitland: It’s like the best Tuesday I’ve had in a long time, it’s important to realize. [Laughter]

David Favela: We’ve got a barrio bird flying up above us, I’m sure chasing somebody. But here in the beer garden, we have peace and tranquility. We have an unusual unlikely combination of really a place that’s safe and comfortable and inviting in the middle of a neighborhood that hasn’t necessarily been considered that in a long, long time. So it’s a very interesting kind of contrast and juxtaposition of two very different kinds of experiences. And I think that’s what surprises people when they come to Barrio Logan, and specifically, when they come to Border X.

Erika Eitland: Well, I feel like one of the things that really hit me is that you’re, I mean, yes, you are the CEO—I love when, you know, a person of color is a CEO—but beyond that, you know, you’re a historian in my mind. And so the other day when we walked through the neighborhood, you had this incredible understanding of Barrio Logan. Like you aren’t just like someone who owns a business here. You know this legacy. And I was wondering if, for folks who don’t know Barrio Logan, you could give like a brief history for them.

David Favela: Yeah. So I’ve, I’ve always wanted to understand why things are the way they are. And history and economics are probably two of the best storytelling techniques to really understand how things come about. And right now we’re in, we’re in Barrio Logan. That was really subdivided in 1881. Originally, it was, you know, farmland and open pasture here in beautiful San Diego. And it’s gone through a variety of chapters. So it had a big boom in about the 1910s, when the Mexican Revolution created a wave of refugees that came across the border. And Barrio Logan was the place that they called home. It wasn’t Old Town. Wasn’t Downtown. It wasn’t the North County, because at that point, it was all pasture land and farms. So this was where those families came for safety and opportunity. And since then, those families have been here. And there was really a heyday—I would say, probably the 1920s and ’30s—when there was, you know, the community was really developing. They had their own dentists. They had their own movie theater. It was really its own community. And it was really strong. in the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s. There was an emergence of social clubs, what they called “jacket clubs,” because they wore jackets. And they’re not gangs.

Erika Eitland: Yeah. [Laughter]

David Favela: People make that mistake. They were truly in the word, and they used it themselves, “social clubs.” And they had super interesting names. One was Los Chicanos. So we can even point back way back when the political days of the 1970s that term was already being used. And they would organize car washes or dances to raise money and then just really enrich the fabric of the community and provide the entertainment and the culture for the community. You know, since then, it’s obviously fallen on hard times. Probably in the ’90s because of drugs and gangs and everything that happened. But what never was removed from here was the people, their families, the stories, and the culture. So when I came along [laughs] in 2014, I didn’t immediately recognize it all because you could drive around this neighborhood and you didn’t see the culture. You saw the graffiti. You saw the street art. But you didn’t understand the depth of what was going on here. And the fact that some of the families in these homes have been here for over two to three generations.

Erika Eitland: Oh wow. Okay.

David Favela: Yeah, I remember when I was remodeling the our first Border X over here across the street in the corner, I was constantly being interrupted by older gentlemen and women who would peek in and see me in my construction clothes all dusty and say, “What’s going on here?” You know, ’cause they’re so nosy.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: But what they were doing is they were vetting me. They really wanted to understand who I was, what I was about, and what I was bringing to the community, because the community is very protective. And so that’s really the history of Barrio Logan, in a nutshell, is that culture established over many, many decades is still here. And as a brewery, we just really sought to create a space for the community to fill with what was already here.

Erika Eitland: Right. Well, what’s interesting, and the way that, you know, you were talking the other day even is that Border X is now a part of that history. It is a part of the legacy of Barrio Logan and the way that this street has even sort of developed over the last 10 years. You know, right now, I’m wearing a shirt that says MUJER YOU ARE WORTHY. And it’s literally from a shop two doors down from a young woman entrepreneur who is like, I want to start my shop here. And I think that’s partially because of something like Border X. So with that in mind, in that history, there’s a possibility for gentrification. And a term that you brought up—it took me a second, I was like, Wait, my Spanglish is good enough, I get this—is “gentefication.”

David Favela: Gentefication, that’s right.

Erika Eitland: And so “gente” being “people” in Spanish, and so this people-ification, and as like a public health scientist, I’m like, I’ve been doing gentefication all my life, and I didn’t have the right term! And so I’m curious for folks, how would you describe gentefication? I think for urban planners especially, they are so fearful of gentrification in their work that they almost are paralyzed to make, you know, truly radical cultural moves.

David Favela: Yeah, you know, I’ve always had a deep interest in economic development. I’ve always, you know, understood my parents, why they immigrated to the U.S., their stories, and how they, you know, succeeded here in the United States. And so I always recognized early on that economics and the capitalist system, for better or worse, is an essential part of our existence. And so I think any strategy of improving people’s quality of life has to take that into consideration. And so when we came here, we still hadn’t fully formed and understood what gentefication was. We just kind of had some ideas. And I think what I’ve distilled it down is there’s basically three things that we try to get everybody on the block to practice. And the first one is very basic but profound at the same time, is that all the other businesses on the block are building businesses for the existing community. And it’s a very simple concept. That is, we’re not waiting for displacement to bring in a new higher-income crowd. We are creating a business that survives based on the locals patronizing that location. And there are a lot of things each of the individual businesses that have done well that have done to attract that local audience. But that’s been a really critical part. And so what makes me very happy is I look around and there are tons of locals here. There are, there are people who come here to have their birthday parties. There are people who come here to have their anniversary, baby showers, just the most unusual celebrations. But you know, we realized early on that a lot of these homes were built early on in the 1910s, 1920s, and just literally don’t have room for family get-togethers. And so we’ve become in a way that, that living room for the community. And so I think again, yes, we serve beer, yes, we serve food. But there is something more that we feed. And I’d like to, without sounding presumptuous, we feed people’s souls.

Erika Eitland: Well you fed my soul. The other day when I had this, this pepino beer that you have, and I took a sip—and luckily I was amongst professionals that I didn’t start crying—because like you are— That is the thing is that when we talk about culture and design, like that is even the flavors that we get to consume. And so I think it’s, it’s the space, but it’s also like, every element of Border X is bringing back celebrating this community. And that is so powerful.

David Favela: It is. And you know, I didn’t realize that aspect you just talked about because I had been in high-tech world in the suburbs for 22 years working at Hewlett Packard. And I came here for an art show once, and I remember feeling something very deep in my heart, my soul, I guess, is a way of describing it, where I saw people of color, doing really cool things creating art, holding events. You know, and I was just like, Wow. I never realized that there was a part of me that wasn’t really being expressed or touched on anymore.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: You know, as an executive at HP, I created a facade for myself that you have to as a professional to survive and thrive in that environment. But there was a part of me that said, Yeah, but you haven’t fed your soul at all, you know? And I think that’s what people feel when they come here and we speak their language, literally, naming the beers—

Erika Eitland: Yeah

David Favela: And the food and the art and the events that we hold. People look at that and they see themselves. They recognize themselves, and they go, Wow, it’s really cool. I’m cool. Our culture is cool. And we don’t get told that enough.

Erika Eitland: I think, you know, something Eunice and I both feel really strongly is that we’re blended, you know? Multigenerational, multiracial, like it is just this— We are the melting pot, they always talk about. And yet, there aren’t a lot of room for melting. And it’s, you know, to come to a place like this where you’re hitting at this intersection of so many different things, that to me is the powerful piece, is the worlds from the demographics, even of this, you know, society is going to become more blended. And the future is things like Border X that is hinting at that intersection. So we got to the first piece—

David Favela: Yes,

Erika Eitland: of what is gentefication.

David Favela: Let’s bring it back to the last two?

Erika Eitland: Yep.

David Favela: Should we?

Erika Eitland: Yeah. I think so. All right. Let’s do it. So number two.

David Favela: So number two is I feel like there’s a serious lack of storytelling about our communities. You know, people really don’t understand Barrio Logan. I didn’t understand Barrio Logan until I came here, worked here learned, you know, met people talked about history that I truly started understanding Barrio Logan and its unique history. But there are stories all across the United States. And the stories that tend to be told are the ones that are, how shall I say it? The more dominant stories, maybe it’s perhaps. I’ll give you an example. When we opened up our brewery in the city of Bell, right across our street they’ve preserved the Victorian home of the original Bell pioneer family. And you’d like to think, based on the stories being told there, that they came to this empty land and through sheer hard work and hustle created something out of nothing. And it’s like, no. Actually, there were the Kumeyaay— Well, there there’s a different tribe. But there were Native Americans. And then, after the Native Americans there were Mexican Ranchito families who had adobes that were preserved—

Erika Eitland: Yeah. Yeah

David Favela: That were razed to the ground and something built on top of it. But you know, that is repeated over and over again. I mean, we looked at Escondido, which is in the north county, and I was looking at a place to potentially open another brewery. And it was this old little corner store called Lopez Market. And it’s where all the farm migrant workers would cash their checks, would buy their tortillas. I mean, I mean, going back for a long, long time, there was even a clandestine poker game in the back room.

Erika Eitland: Okay.

David Favela: And, and it’s so symptomatic, I think, especially in urban planning, that that was razed to the ground. I was trying to save it, and I was going to build a brewery around and just have— use that as a platform to tell the story about migrant workers in that city, who, frankly, were the economic engine. Yes, the ranchers owned the properties, but the people who worked the land?No one’s telling their stories.

Erika Eitland: Right.

David Favela: And, and in the ultimate of ironies, the planning group of that city had a brilliant idea. They were going to redevelop that whole section, and they were going to call it the “Mercado District.” And it was going to be celebrating the colonial romanticized past of Mex—, of California. [claps] And it just felt like a stab in the heart. It’s like, because it’s, it’s being standardized in a way that’s romanticized, nostalgic, and totally removed from the Latino guy who’s walking down the street, whose parents or grandparents used to be migrant farm workers. There’s no connection between him and what they’re trying to do. So we’ve been kind of, there’s this chapter of just the common person, the hard-working person that’s helped build this country—

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: And they’re invisible.

Erika Eitland: Well, and I think that’s so powerful, because it’s the power of who gets to share their history and who doesn’t and whose history is erased. Like, I love this line, “Our history is our prologue.” Like whatever our story is, it is sort of informing where we have come to today. And if we don’t actually acknowledge that we miss a critical piece of information, evidence, details, all of that. So—

David Favela: Well, it’s so critical to forming a strong sense of self, to understand who you are, where you come from, the role of your ancestors, and whatnot. And when you don’t have that, you become unmoored in a way where it’s like, Well, I’m just whoever I am, and I’m just here, and there’s just, I popped in, because obviously I study history in school, I walk around the city, but there is no mention of anybody or anyone that I know of. So I think gentefication bringing it back, is really about—

Erika Eitland: We have number three still. [Laughs]

David Favela: Yes, so, but in summary, the second one is the businesses have to tell those stories. We have an obligation. And I think when you walk up and down the street, when you have someone who can help you decode the street art, the paintings, the names…. There are so many stories. I had to rush through it, but I could spend like half a day here talking about this building and that, that building. So it’s, that’s really, I think, an obligation of when we think about economic development and redevelopment and urban planning, you know, don’t erase it. You know, tell the stories that aren’t always being told and tell it in a way that that still connects to the people whose ancestors were there before. So that’s the second piece. The third piece is really going to the heart of economic development. And there are so many different models from an urban-designer perspective of, Well, how do we create jobs? How do we create economic activity? And really the shortcut is, We’ll just work with franchises, just work with big-box stores, just go with what’s known. And I understand that. Sometimes that is the more likely to succeed, the more—

Erika Eitland: Path of least resistance.

David Favela: Path of least resistance, and you know, these are all proven concepts, they just need a physical space to occupy and they should thrive. But I think what that totally ignores is as you do that more and more, the opportunities for true grassroots entrepreneurialism actually diminish. And we were faced with that on this street. So interesting enough, you know, there’s a gentleman here in the community named Chris Zertuche. He managed La Bodega art gallery. He had this—and I didn’t understand it at first, but I can see how it was such a critical part of how we evolved—is he actually worked with the landlords on the larger properties and subdivided them. So if you had a 5,000-square-foot retail location, there was no one on this street with a business model—

Erika Eitland: Oh, to pull that off.

David Favela: Or the resources to pull that off. But there were 10 people who could if they all took a little piece of that. And by doing that—and I think there’s at least three or four buildings that are like that, where they’ve been “activated,” we call it—in a way that now these young entrepreneurs can plug in, and many of them have created thriving online business stores—you walked in and bought this beautiful shirt—

Erika Eitland: Yeah. Yeah. [Laughter]

David Favela: And so now we’ve got, you know, instead of just one large retail location, we have 10 small artisan, craft, you know, cool shops. And that’s added so much texture and culture and beauty to the neighborhood. And personalities. And you know, people who frankly, have enriched things for all of us. I mean, I think you’ll recall, when we were walking through, I waved to a young lady in a small shop,. That’s her shop, we call it Sew Loka. Sew “loca,” crazy.

Erika Eitland: That sounds like Eunice and I’s friendship. Sounds right.

David Favela: And she has taken over that spot. And I very publicly credit her with the courage during the pandemic to step up and say, “Hey, guys, you know, we got shut down in March. We kind of weren’t sure what was going on. And I think in August, when we were looking at another shutdown, she said, “No, we’re not just going to wither away and have this beautiful thing that’s happening on the street get destroyed.” And she said, “We’re going to do this thing called Walk the Block. And we’re going to put our shops out on the sidewalk. And then people don’t have to come inside. Everything’s outside.” That first weekend we did that, our sales were three times what they had been before. I mean, there was such a great vibe on the street. People were out and about, and we all kind of needed that after the pandemic. And it’s still to this day contributing tremendously. So she may have one of the smaller shops on the street, but ideas don’t know the dimensions where they originate from. And her leadership and courage are things that have benefited me, the largest business on the block. So I always make sure to give her credit, but it’s just a great example, I think, of something we may talk about later, which is this whole collective action really on behalf of large, medium, and small shops here on the street. That we’ve all helped each other in one way or another.

Erika Eitland: Yeah, definitely. What I think is hitting for me is that— So I live in a very rural town, and yet this idea of breaking up the 5,000 square feet to give that empowerment to smaller business owners who have all of these ideas and creativity, that becomes their platform to make change and on a scale that works for them.

David Favela: Totally.

Erika Eitland: And so I just feel like although we think of this as urban planning and urban design, what’s funny is if we break it down into our neighborhoods, if we think about the gente, like it becomes a different thing, where even in rural communities where they might have sort of these dying main streets, the same thing is so true. And you wouldn’t call that maybe urban design, but it is, you know that happening in those places as well.

David Favela: Oh, it is. It is.

Erika Eitland: Okay, so to break it back down. Our three things are that we should remember for gentefication—if you were to like single sentence—what would it be?

David Favela: Make products or services for the people that live in the community. Celebrate the history and tell the stories of the community. And create economic opportunity for people in the neighborhood. A lot of these businesses are from people from the neighborhood, and I think that’s really important. Because we’re not trying to displace them as we try to evolve the neighborhood. We’re trying to bring every, as many of us along for the ride as possible. And so the more slots that people can plug into— And by the way, we not only do that, but here at the brewery, we hold markets and small craftspeople and small artists and we don’t charge a commission. And so we try to support it in all different aspects.

Erika Eitland: So gentefication is sort of our, our central framework for this conversation. How does this actually stimulate greater conversation? How is this just the beginning point? Because this isn’t just about, you.

David Favela: No.

Erika Eitland: This is about the communities that you are in. It is about bringing them in and them kind of guiding you from the word go?

David Favela: Well I think, just like any market, there’s always the concept of what they call the anchor store, or the anchor retail location. And in a way we became that. And I think any essential economic redevelopment plan has to have a few big bets. We were definitely a small bet that grew into a bigger bet.

Erika Eitland: I think what’s crazy about that even is that we’ve all talked about food desert, but that idea of like having and creating places where there is joy and fun and that bringing those folks together is something we sometimes take for granted because we see food as like this human right. But like why can’t joy it and coming together be that way? Brewery deserts are a real thing.

David Favela: Yeah. So one of the things we quickly realized when we first opened in Otay Mesa, in an industrial park, that if you drew a line, latitude line from Downtown San Diego and said there’s North San Diego County and South San Diego County, you would have found nearly, what was it? 85 breweries north of Downtown. You would have found one or two tiny breweries south of Downtown. And what’s the difference? South of Downtown is towards the border, towards the Mexican border, predominantly Latino community, multicultural communities. And there was nearly a million people there. And so they were being dramatically underserved. If you were growing up in any of those communities and you wanted to go have a brewery experience—and at that time there were hardly any Downtown—and now there are, but 85 breweries north, especially North County, which is a full almost hour drive if you lived in South Bay, and we realized when we kind of tap— opened our brewery that we had tapped into this like underserved market. Like we had a line literally the first day we opened. We rolled up the door, my brother and I, and there were like 50 people waiting to come in. And we had never served anybody. We had never tapped a cake since college days.

Erika Eitland: [Laughter]

David Favela: It was just really craziness. But it really that was kind of like one of the first lessons I realized, and as I reflect back on it, is that there are tons of underserved communities out there where people have a lot of assumptions that either, Oh, Latinos or people of color don’t drink beer or craft beer, don’t want comfortable, safe, fun environments where they can come with family and friends, aren’t going to be willing to, you know, pay slightly higher prices than a malt-liquor store, you know, on the corner. And they’re all false.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: They’re all false. We’re all human, we are looking for connection and an opportunity to enjoy each other’s company. And I feel when we expanded to Los Angeles, we were absolutely opening up in a brewery desert. You could go to Google Maps and just put breweries and you could see us just like this lone— And people would tell us, they’d say, Thank God you opened up here, because otherwise we’d be driving 30 minutes and all around in order just to go to a great place. Now I just walk down the street or, you know, I can take an Uber here or whatnot. And I think that says a lot about how people perceive our communities and perceive people of color and lower-income people too as well.

Erika Eitland: Yeah, definitely. It’s almost like this spatial epidemiology that’s happening. You know, where is— Where are food deserts? Where are brewery deserts?—with assumptions that are biased by how we’re interpreting that information, whereby we don’t think those people need it, so it’s not really a desert. But it is.

David Favela: It is.

Erika Eitland: And so I’m curious, you know, as we think of this through a lens of restorative justice, how do we quantify something like the success of Border X in all of its locations? What are those metrics of success That make it easier for someone to embrace gentefication in a real way?

David Favela: Yeah.

Erika Eitland: Because what I hear from like a public health side is, Oh, well, it’s hard to, you know, quantify health and spaces. Energy efficiency: so easy. And it’s like, Nooo, you can’t quantify health.

David Favela: [Laughter]

Erika Eitland: I believe in us. And so for here, you know, what do you think are maybe some of those metrics of success—

David Favela: Ohhh, yeah

Erika Eitland: That we can sort of look to and say the success of Border X is not just feeding your soul, but there are these real things that you can look and start to measure and know that things are changing. And maybe it’s even pulling from your background in economics where it’s thinking about the streets and the types of businesses? How do we get that—

David Favela: Great question. So I think, you know, I’ll start with the easiest to measure because we always do gravitate towards that. I grew up in Hewlett Packard, and you know, if you know the origin story of Dave and Bill—

Erika Eitland: No, I don’t actually.

David Favela: Yeah, they started in a garage.

Erika Eitland: OK.

David Favela: But they had a very profound humanistic way of approaching technology, businesses. They say the whole thing about Silicon Valley and the creation of that technology and a kind of a business environment that was more open and creative?

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: But you had a really famous saying that I kind of took profoundly, which was, Our company aims to do well for the community and our country and the world. But it has to do financially well in order, in order to even be here to to well. So to me it’s like I can talk about all kinds of things, but if I don’t survive, if I don’t succeed, then this is not a sustainable model. So I think the first measure is, are you a successful business number one. And that’s just measured in, you know, cold, hard numbers. After that, though, I think it does touch on the more softer side, and they’re not quantifiable in such a way. I can tell you the one that means the most to me is, I am happiest when my brewery is full of people from the community but also from other communities and there’s this incredible blending and incongruity of different people from different walks of life. I remember, on Thursday nights, we have a Latin jazz jam that, you know, brings retired white bankers from La Jolla, you know,

Erika Eitland: Hoh-kay.

David Favela: Super wealthy. And then there’s a motorcycle-club member with tattoos all over his bald head and a six-inch knife hanging from his shoulder. And they’re both grooving to the same music and having a good time. And we’ve never had an issue, and it’s— There’s a very interesting kind of tension, not in a negative way, kind of like this, Hey, we’re, this is different. It’s not a nightclub. It’s not a bar. It’s not a— You know, we’re all here because we, we just want to relax and enjoy ourselves. So we don’t, you know— For being in the heart of the barrio and in what some consider a fearsome barrio, we’ve never had, you know, nine years, hardly any issues. I mean, it hasn’t been zero, but it’s far below anything you’d find in even Downtown San Diego, where there’s a ton of restaurants. We have far less than that.

Erika Eitland: Well, what’s interesting—and I think it came up the other day when you were talking—there is such a respect for this. And so I’m curious, as you were earning that respect, what challenges or barriers did you really have to overcome? And what were their sort of, I don’t know, reservations before really accepting you into the community?

David Favela: Such a critical question. Like I said, Barrio Logan has been here for generations. And as part of that they are very protective and defensive about what goes on in their community. And they have ways of controlling what goes on in their community, everything from civil disobedience to other things. And, very interesting, so we didn’t have a lot of money when I opened up the tap room here. And I did a lot of the work. I’m very handy. I do construction, carpentry, all kinds of stuff. And so I would be there, as I mentioned, covered in concrete dust or whatnot, and when some of these elders would come by—and I’m talking people in their seventies and eighties—and would just randomly stop me, I’m like, Ah, okay. I’d talk to them, but they were vetting me. They were, Okay, who’s that guy? What’s he doing? What’s his interest?— Oh, no, he’s doing all the work. You know, he’s told us about his vision, his dream about opening up this brewery and, and, you know, without knowing it, if I had shown up with just bags of cash and hired a bunch of contractors and sat there in a suit just supervising people do the work.—

Erika Eitland: [Laughter] Yeah.

David Favela: I think it would have backfired, to be honest. I think I might have been run out of the neighborhood, to be honest. But I think there was a certain amount of respect that they saw that I was there and that I came from as humble origins as anyone else. Snd they respected that. That was really, I think, the foundation of why I was allowed—

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: To open in the neighborhood. But then I think I’ve proven myself through my actions. And what I, what I tell people and you know, and explain to them why we come here and why we do the things that we do and, and why it matters. Because I would say that there was a tipping point where, because it’s such an activist community, that there were a lot of people said, “No, no, no breweries are all about gentrification. You’re just the shock troops of the real estate agents. And soon this whole place will be transformed, and we’ll all be displaced.” And I met with them. I said, “Don’t throw rocks at my place. Don’t spray paint.”—

Erika Eitland: [Laughter.]

David Favela: Let’s meet. Let’s talk. And I think you know, after having discussion, saying, look, and my basic point has always been the same—

Erika Eitland: How many meetings did you have?

David Favela: Oh, my God.

Erika Eitland: Like, how long did this go on? Because I feel like you’re like going through this, and I’m like, nothing happens in one good meeting. Like—

David Favela: No, it never— It’s really about consistency and walking the walk.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: Because anybody can talk the talk. It’s really being there. And they see that. And I think there’s a tremendous amount of respect. I mean, I had meetings from, like I said, with these elders to even one day, I remember coming back here, and I, I— There was a few gentlemen at the, at a table. And I had asked them to please if they could be quiet, because we were doing an interview or whatever, and, and everyone was really . And I was like, Oh, shoot, like—

Erika Eitland: Oh, no.

David Favela: Cause yeah, three of them looked very normal, you know, middle-aged Latinos dressed in normal, no visible tattoos or anything. And there were a few others that were a little bit more gangster. And, and I remember that they were asking me questions about why did you come here, what is going on. And it kind of suddenly snapped into focus that I was talking to what are called the “shot callers” of the neighborhood, the people who control mostly everything. And an incredible peace came over me—no fear whatsoever, which was unusual. I should have been scared. But I was just upfront and honest about and I said—

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: Look, I think this is really important for our community. Yes, it is changing. But I think if we can control the change, if we can be part of the change, I think we all have a role to play. And, and you know, that that was enough for them. And it was really interesting. So, boy— [Laughter]

Erika Eitland: [Laughter] That’s an important stamp of approval. My gosh. I, you know, something I’ve realized— We’ve been chatting for I don’t know how long now, and we’ve talked about the macro stuff. We’ve talked about the community level. We’ve talked about, you know, gentefication. We’ve talked about relationships. We’ve talked about people down the street. We actually haven’t talked about the beer.

David Favela: [Laughter]

Erika Eitland: And what’s so interesting about the beer in my mind is that’s a design decision. So you were nominated, did you win this James Beard Award?

David Favela: Semifinalist.

Erika Eitland: Semifinalist! We need that dinner at some point.

David Favela: Which is huge. Yes.

Erika Eitland: But what I think is so special about that, that is also a design decision—

David Favela: Yes.

Erika Eitland: Of really bringing culture into something and creating something for human consumption, spaces about human consumption, and how we use it and experience it. And beer is no different. And beer just heightens our senses. And so I’m curious, you know, of some of the beers that you’ve been brewing here, what are they? What makes them special to you? Because I think that’s what brings people in is actually the beer that they’re drinking is, you know, that ratatouille moment. When, you know, the little mouse feeds that, you know, crazy critic, and all of a sudden you’re like, transported back. And I think, you know, even for myself, being Bengali, like, you know, that cucumber beer, when you have it, it’s just such a universal flavor. And I was like, I don’t know, my feelings. I feel them so strongly now. So I’m curious, you know, A. what was inspiration? that B. Like, what are some of the ones that you were just so proud of to know that we now have a beer of that?

David Favela: Well, you know, I think there were a couple things that were at play. I remember being profoundly influenced by a book called Blue Ocean Strategy. It’s a business book. And it basically talked about, you know, how certain industries get commoditized, and the existing players in that industry just try to outperform each other on the exact same vectors that they already were on. So, for example, they use the case of circuses. So they talked about how Ringling Brothers and Circus Vargas got into this whole big-animal competition. So they’re like, Oh, someone’s got a Siberian tiger? We’re gonna get three of them! And so they just kept upping the ante and never really thinking about what it was that they were doing or providing their customers. And there was a small circus in Quebec that said, You know what, we’re not going to have any animals. We’re gonna— It’s gonna be a human-based show because animals are very expensive and dangerous and it’s cruel and we’re just not going to have it. Period. So they make very dramatic decisions.

Erika Eitland: Eunice is Canadian. Do you know this story?

Eunice Wong: No.

All

[Laughter.]

Erika Eitland: She doesn’t. Oh, it’s an education for all of us.

David Favela: So this little circus troupe— I think they started off in a park or something. It was gymnasts and performers and they would— And they said, Look, you know, we’re not gonna have animals, but we are going to do, because this is what people want, is we’re gonna tell stories through our acts in our, in our storytelling. We’re going to do it in really comfortable environments, whether it’s a fancy tent, or whether it’s Las Vegas. And we’re just going to create this beautiful experience for people because they’re coming for entertainment. They’re not coming necessarily for a Siberian tiger. And that little circus is Cirque du Soleil.

Erika Eitland: Oh, wow.

David Favela: And now they’re about $2 billion, where most of the U.S. and global, and have it installed, based there in Las Vegas that’s always sold out. And it affected me profoundly, and I go, Well what does that mean to me?

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: And from a brewery perspective, I said, I’m not going to compete with everyone else trying to make the best IPA in the world or the best lager that— [Hits table.] Been there done that.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: And everyone else is saying the same thing, Oh, my IPA is the best, so— They’re all great.

Erika Eitland: I don’t like IPAs, so they’re all bad. But that’s just me. [Laughter]

David Favela: [Laughter] So we took a very dramatic decision early on, and we said— And the other piece of it was, we were sitting around the table looking at each other drinking Irish reds and Scottish stouts And this and that, and we’re like, What the hell are we doing?

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: This is like, We don’t know anything. We’re not, we weren’t raised in that cultural context. We don’t have any ratatouille moments of experiencing these beers. Are they good? Can I learn to like them? Absolutely. But they’re not connecting in a meaningful way to who we were. And I remember we made a very profound decision— This is right when we opened, right before we opened, and my nephew walked away. And we said, Look, we’re gonna make Mexican-inspired craft beer, because we’re Mexican, and at least we can be good at that. [Laughter]

Erika Eitland: Yeah. I love it.

David Favela: And so, but we still— That was strategic. It wasn’t tactical. It’s like, Okay, so what does that mean? So I credit— Challenge accepted. Challenge accepted. So my nephew went off and came— We met back up in about three weeks. And he brought this little keg and he started serving us in the meeting. And it was this beautiful ruby red beer with almost— It was so red that the phone was like pink.

Erika Eitland: Oh wow.

David Favela: You know? And I’m like, I’ve never seen a beer like that. And he’s not saying anything. And we’re drinking it and the hibiscus and the tanginess, and we’re like—

Erika Eitland: [Laughter]

David Favela: This is agua de jamaica, which is a very traditional Mexican drink. And I’m like, This is us! This is us.

Erika Eitland: And it’s a saison.

David Favela: Yeah, and it’s a—

Erika Eitland: Which is a lovely, like, farmhouse brew. And it’s like, yeah—

David Favela: Totally.

Erika Eitland: Like, all of that, it’s just like—mm. [chef’s kiss]

David Favela: And that beer, that fateful beer was the decision and became our top seller for like the first two to three years. And then we built on it by adding Horchata Golden Stout; the Pepino, which you enjoyed so much; Abuelita’s Chocolate.

Erika Eitland: Mmmmm.

David Favela: But you know, so that’s how we arrived at kind of making that strategic decision. I think, though, once we started pouring the beer and allowing our customers to experience it, I realized something very profound that, again, organic, not consciously choosing it, but in a way we tend to be as a minority, a person of color— There’s a term called a “colonialist mind” or “colonialist mindset,” where we are told what is good.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: Well, what’s the best cuisine in the world? French, of course!

Erika Eitland: No debate! [Laughter] And so there’s this whole series of ideas and concepts of where we think of in terms of excellence and best in class. And I think when we decided to focus on our own culture and tell the story of our flavors and our experiences, and we put it on the same pedestal as all these other cultures out there? In a way, we were decolonializing our minds and saying, We matter. Our tastebuds matter. Our traditions and culture matter. And, and we think other people might enjoy it, too. And I think it’s had this really profound experience when our customers come in, and they’re like, I grew up drinking abuelita’s chocolate! Or, Oh, my God, I can’t believe this horchata’s so good! Or— And we’re having those ratatouille moments because we’re connecting nostalgically, but also kind of spiritually with, again, the same theme: You are cool. The things you grew up with are cool no matter what your socio economic standpoint. We’re celebrating the humble. We’re celebrating the everyday. And I think we don’t do that enough. And I think as people, it stunts our personal growth when we can’t celebrate ourselves or our families or those things that make us uniquely who we are.

David Favela: Yeah.

Erika Eitland: I think what’s so powerful about that is that is what this— So we were at the National Planning Conference here in San Diego, and everyone’s talking about inclusion and everyone’s talking about accessibility. But what you were talking about that is at a radical personal level that is like what we are trying to aspire to—

David Favela: Yeah. Yeah.

Erika Eitland: And it is being missed. And yet I think one thing as a person of color, as a woman in the sciences, it takes so much courage to put yourself—your full self—in that pedestal and say, I am as worthy as the others that are beside me. And I’m wondering, like, from your own wisdom, as an executive, as a construction worker covered in dust out here, as the one leading some of these community discussions with some interesting people, what would be sort of your words of advice to those people to give them courage? To be able to say, “I’m going to be my authentic self”? Because to me, and I think design is only strengthened when everyone brings their authentic self. And I think we’ve all quietly live in that colonial mindset and are starting to unlearn it. But it takes courage to even embrace it.

David Favela: Well, I think sometimes, if I were to outline a map—and by no means am I a model to follow, because it took me like 53 years to figure it out [Laughter]— But if you want the shortcuts, I think, really understanding yourself and why you hold certain things— Like where do you get your ideas from? Like your beliefs of what’s good? what’s bad? of what’s cool, what’s not? Is really questioning where that’s coming from. Because I know, growing up, like, we would, I would reflect on, Well, we were lower income, my dad was a gardener, my mom was a housewife, we didn’t have much, and there was a shame almost— I still remember middle school. My dad would drive this old landscaping truck, you know, the Chev— a green Chevrolet. And I would almost ask him to drop me off a block before so he wouldn’t drop me off right in front of the school, ’cause it was shameful.

Erika Eitland: [Laughter] Here we are though! We get there! Yeah.

David Favela: And somehow— And I’m not sure how we can pierce that veil of falseness that, you know, there’s no shame in that. And, and there are people who accomplish this naturally. I don’t know how. They have this natural sense of confidence and pride in who they are and what they’re about. And I think for the majority of us, though, it takes a little bit of time to pierce that and really kind of be comfortable in your own skin and be comfortable where you come from and who you are and what you’re about and really understand, you know, are you simply adopting other people’s perspectives and, you know, playing them to yourself? Or are you truly yourself?

Erika Eitland: What I think is interesting, though, and I’m like— I agree. But I’m also not letting you off the hook, which is—

David Favela: [Laughter.]

Erika Eitland: The fact that, yu know, to me, I think that’s, that’s true. But like, for the woman who I bought the T-shirt from down the street, you are critical reinforcement for her to have that courage.

David Favela: Oh.

Erika Eitland: And so in my mind, like, what are those reinforcements? Because I would say, based on my understanding of ,the field of design, architecture, urban planning, all that it’s still a white male leadership. And yet tides are changing. But where, where do we provide reinforcements in that courage and in making that feel welcomed and included and accessible in the way that you were talking about?

David Favela: Actually, you raise an absolute phenomenal point, which is the power of inspiration. And, you know, I, I may have influenced some people positively, hopefully, on this block and beyond.

Erika Eitland: I mean, I’m on this block and I feel very inspired, so—

David Favela: [Laughter] But I’ll tell you, my inspiration came from the artists. And I remember very, like I was mentioning to you, I was, I had been in high tech 22 years. I’d been doing this thing, and I still felt kind of hollow inside, though, in a way. Because I couldn’t ever express anything about who I was or where I was from. I had to almost have this facade to succeed. And you just got better and better at putting on this imposter. I mean it’s—

Erika Eitland: Code switching.

David Favela: Code switching and just like this, this very strange thing. And sometimes you have to focus so much on it that—

Erika Eitland: Exhausting.

David Favela: It’s exhausting, and it just overtakes you.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: And I remember going to this art show—and I think artists are uniquely positioned to do this—is I saw young Latinos, people of color, creating really cool artwork. I saw that they were expressing it in their clothing. Like they were fully comfortable. They may not be economic successes, but they were fully comfortable and confident in who they were and what they were about. And there was just this sense of like, Yeah, we’re Latino and it’s cool. And look at what the, artwork we’re creating. Isn’t that cool? And look, we’re also creating music. Isn’t that cool? And, and all of a sudden, you’re like, Oh, wow. You guys are creators, you know. And I think I was inspired by that. And I tell people that you know, there was this place here in Barrio Logan called the Roots Factory. And they would like take random empty buildings. They would not—I don’t know if they leased them—they were, there were a lot of random empty buildings, but— They would have concerts, art shows. It was kind of like this whole underground scene.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: And I remember how much that filled me with pride, with inspiration, with like, Wow, this is really awesome. More people need to experience what I just went through.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: You know, because I think that changed me profoundly. And I mean I left the corporate job a few years after that initial experience and decided to double down here at the brewery. So I think you’re right. I think we find inspiration from a variety of sources. To me, though, the ones that inspire me the most are the ones who are taking their experiences and transforming them into something beautiful. And especially Chicano artists I really enjoy, because they create artwork that, really for me, that I understand. They’re— You know and I imagine for you as well us there’s cultural symbols and backgrounds and stories, and you’re like, Oh, I see that in that art piece, but no one else does. It’s like a secret decoder ring. We have this like cultural background that some people may see one thing and you’re like, Oh, wow, that’s so profound. You know?

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: It’s so wild. But that was actually my initial inspiration to really think more deeply about Border X. I mean, we had already been making Mexican-inspired craft beer, but we really lacked that second layer of creativity and culture and all of that.

Erika Eitland: So for people who are listening, we’re in this beautiful outdoor space. We’re under these lovely sort of shade protectors. But there is art all around us, you know. And who are these artists that are sort of decorating the walls as soon as you walk out back here?

David Favela: They’re all local artists! You know and it’s like I told you earlier, we created an empty space, and people filled it with culture and beauty. And that was hopefully my business model everywhere I went. But I’m finding that different communities have different levels of expertise in that area. Barrio Logan is blessed with an incredible community of artists and musicians. Most of the musicians that play here are from the neighborhood. And I mean, yeah, and our tap room is filled. I mean, the tables are painted the walls, we have rotating art shows. It’s just you walk into an experience, and I think that’s what has made us such a success is I think people come in here and they’re like, Wait a second, this isn’t a taco shop. This isn’t a brewery. This is like a whole different thing.

Erika Eitland: Yeah. Well, I think what’s funny is, is you’re sort of talking about bringing this beauty to the brewery. There’s something about it, where it’s a little bit edgy. It is cool. It is all these things. And so even that like pure definition of what beauty is is in the eye of the beholder. It is the chameleons among us. It is about sort of being blended and just like seeing these beautiful things that are so beautiful to you. And you don’t actually need anyone else to see it. You just need to—

David Favela: Yeah.

Erika Eitland: And I think that’s hitting home for Barrio Logan residents who are coming and all of us who aren’t from here, wanting to be a part of it with you.

David Favela: Yeah. No, and I think— And this is going a little bit profound and hopefully I will, it’s not thin ice. But I think you know, being a person of color, that in a certain way were traumatized. You know, I know I’ve had my experiences growing up where I suddenly was reminded I’m not— I’m different. And even though I felt like I was just American, I knew that it wasn’t always the case. And when you come into a place, like you said, that 1. the beers are award winning, recognized James Beard Award. It’s like it’s excellence!

Erika Eitland: Excellence.

David Favela: And you’re like, That’s, that’s me, too. That’s my culture! And then when we put artwork, which is also excellence, they’re like, Oh, yeah, that’s, they’re talking about me! This is my culture. Then you hear the sound of the music and Spanish, because we tried to play local music in Spanish and, Oh, that’s so freaking cool! And—

Erika Eitland: [Laughter]

David Favela: And in a way it’s, it’s healing. It’s really healing. So you were talking earlier, like, what’s the secret to kind of become more self aware, more fully yourself—

Erika Eitland: And courageous, yeah.

David Favela: And courageous? Is like being inspired by the way others dress, the way others act, the way the artists make their artwork, the musicians make the— And they’re in that same process of becoming fully themselves through their art and their music and our beer. And I think it just kind of, I think it is inspiring.

Erika Eitland: Well, and I think, as I like, walk away from this conversation, this isn’t a story of oppression. It isn’t the story of health disparities. It is of excellence.

David Favela: Yes!

Erika Eitland: I think we have to, again—designers, planners, all of us—we have to flip the script.

David Favela: Yes.

Erika Eitland: It has to be about elevating excellence. And I just— That is something we have gotten, you know—We will teach history and it will be about slaveryb but not about Black excellence.

David Favela: Yes.

Erika Eitland: You know, we’ll talk about out sort of encampments, and it’s not about sort of Asian Americans, who are killing it. Like, to me, there’s just so many opportunities for us to flip the script. And I do think Border X is a part of flipping that script. It is about excellence. And so … Is there anything else you want to share?

David Favela: If there was one thing I’d love to talk about— Let me just organize my thoughts around it, um. You know, it seems like— I’m really trying to understand what I want to do in my next phase of my life and really trying to take these experiences and transform them into something beneficial. And it’s kind of like I almost have to go back and state the root problem, which was, I think, that in order for a country to be successful, for a community to be successful, for individuals to be successful, it’s defined by how many opportunities collectively we create to allow people to grow. So the problem statement is, you know, are we providing those opportunities for people from low income, from underserved communities to be able to help themselves? And I think there’s an educational path, there’s a vocational path, and there’s an entrepreneurial path. And obviously, people can choose to be priests and other things, but we’ll focus on the the first three. And especially the last one, the, the one entrepreneurial path is what are we as a society choosing to provide these communities as far as an escalator, a path upwards? And it’s a messy science, if you will, because we as humans are so messy. We have our traumas. We have our issues. We have all kinds of stuff. And so even as I think, well-meaning agencies, an SBA or a nonprofit tried to develop the capital, the human capital, of these communities, it’s hard. It’s hard, because I think you have to combine a variety of hard and soft skills. It’s self improvement. It’s confidence. It’s inspiration. And I think Barrio Logan, if anything, kind of provides this really unique combination of things—

Erika Eitland: Yeah. Yeah.

David Favela: That, you know, the question I want to focus on moving forward is what were they? Are they replicable? Can we scale these to other communities across the nation? Because I think, you know, as you look at the age demographics and racial demographics across the United States, there’s a huge population wave of Latinos and other ethnic groups coming up. And, and the thing is, if we’re not developing that human capital, we as a country will be worse off. It shouldn’t be seen as charity. It shouldn’t be seen as just, Well, this is a nice thing to do. This is an essential thing to do if we want to provide the kind of quality of life and economic development as a nation and not create dead zones where all these young, capable people are being wasted.

Erika Eitland: What I love, the other day you said, You know, this is Chicana 2.0.

David Favela: Yes.

Erika Eitland: It’s happening. And I wonder if you can, like, explain what Chicano 2.0 is because I think it’s powerful.

David Favela: Yeah, so you know in the 1970s, there was a political movement called, you know, Chicano. But again the term goes way, way back when. I mean back in the 1920s, ’30s, there were clubs, jacket clubs. And so, you know, no one knows exactly where the term came from, but at least when it came in the 1970s—and there are a variety of definitions—being Chicano means you are of Latino, in some cases, Mexican descent, but most importantly, that you’re politically and culturally aware of your position within society and the things that have either come to help you or harm you. And one of the, one of the goals of the Chicano movement was to gain political representation, to have a voice. And they did. They did marches. They did protests. They demanded justice and things like affirmative action and equal opportunity. And all these things came out of that movement and political representation. So now, if you look at cities across southern California, you’re seeing city councils that are made up of Latinos, mayors—case of Los Angeles. And so in a way you can say, Check. This movement has achieved many of its objectives. There’s one objective, though, which was never addressed, and that’s the economic development platform component. It still references the original Chicano movement plan. I forgot the exact title. I want to say Plan de Ayala, but I think it’s actually a treaty or something else. But it still speaks to agrarian reform as the economic platform of the Chicano movement. And I don’t know about you, I love gardening, but I don’t want to make a living with gardening. It’s a very hard thing to do. And I don’t think we as a community understand that, you know, political representation is good, EOP affirmative action—which by the way, I’m a child of; I mean, I was a complete loser in high school and there’s no reason I should have went to college, but luckily I proved myself once I did!

Erika Eitland: [Laughter]

David Favela: And I think that there has to be in this Chicano 2.0 a conversation—which I’m thinking about sponsoring but I’m hesitant—around what does this really mean? And I remember it quite distinctly, because one of the impetus for that is I came to the barrio originally out of Hewlett Packard, wearing a sports jacket as I would been from HP and a good executive, and, and there was a sense that you couldn’t be Chicano and be that like I was. And I was like, Wait a second, I am a child of the Chicano movement. How can I not be Chicano? And I think we need to have a conversation around what that means and what do we need to demand and build for our communities so that we can economically move forward. Not politically, not just through the educational path, but through this entrepreneurial path. And I think Barrio Logan is a great example of something I would call almost Chicano 2.0. And the hesitancy is I know, it’s gonna unleash a firestorm of using that term and then putting 2.0 behind it. But a part of me is like, Good.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

[Cue in “Dia de Playa” by Timothy Infinite / Epidemic Sound.]

David Favela: Good. Let’s have that conversation. Because we’re not having it today. It’s static. It hasn’t changed in 50 years, and we’re still talking about agrarian reform.

Erika Eitland: Now, what do we want to tackle? I got ideas! Oh man!

David Favela: [Laughter] Wow, that was so good. Is it being recorded there, or where …

Yanel de Angel: David Favela is the CEO of Border X Brewing and the director of the federal Build to Scale initiative at the University of California, San Diego. He’s a first-generation American of Mexican ancestry, who created a brewery and an art space attuned to the culture and people who have lived in Barrio Logan for generations. And that’s it for In the Beer Garden with David Favela and Inhabit Summer Jam. You can hear all three episodes as well as the pilot series on our website or wherever you get your podcasts. If you like what you’re hearing, write us a review on Apple or send us a voice memo at inhabit.podcast@perkinswill.com. We want to know what you think design is. I am Yanel de Angel, and I think design is inclusive co-authorship! El diseño es co-autoría inclusiva.

All: [Laughter]

Erika Eitland: Okay, I have an important question, though. Is there any chance we can have a little pepino beer?

Eunice Wong: [Laughter]

David Favela: Of course! Are you kidding me?

Erika Eitland: Okay, you know, this is our last day here and I just feel like it’s important.

David Favela: I got you guys.

Erika Eitland: Inhabit is a production of Perkins&Will. I’m Erika and

Eunice Wong: And I’m Eunice Wong. Check out our show page at inhabit.perkinswill.com for the show notes, music, and links to all of the resources and references we mentioned. Follow us on Instagram @perkinswill.

Erika Eitland: This scrappy team is led by Dr. Lauren Neefe, our executive producer who also edits the show. Shout out to Julio Brenes for the illustrations you see on our website. Music by Epidemic Sound.

Eunice Wong: A special thank you to David Favela for inviting us with open arms to Border X Brewing and sharing his inspiring story with all of us. We’re so grateful for your time.

Erika Eitland: And thanks to our advisory board for being straight with us once again: Casey Jones, Paul Kulig, Yehia Madkour, Angela Miller, Rachel Rose, Kimberly Seigel, and Gautam Sundaram.

David Favela: [Sighs]

Erika Eitland: Ready, Eunice?

Eunice Wong: Yes, the moment.

Erika Eitland: The moment! Ah. Cheers!

David Favela: Appreciate you guys. Thank you.

Erika Eitland: Same. [Gasps] Ahhhhh!

All: [Laughter]

Erika Eitland: Okay, what do we have here?

David Favela: So I just brought out [Can cracks open] This is our special Border X growler with pepino sour—

Erika and Eunice: Ohhhhh!

David Favela: So very limited edition … for each of you.

Erika and Eunice: Oh my god.

Eunice Wong: Best day of my life!

[“Dia de Playa” fades out.]

Erika Eitland: Best day. Oh wow. I don’t know. This will like, this will sit with us and we will marinate in this day for a while.

David Favela: [Laughter] Good. Well, I think very timely for all of us.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: It’s time to I think all of us to recharge our mojo.

Erika Eitland: Yeah.

David Favela: [Laughter]

###